A couple weeks ago scientists in Europe announced that they had sequenced the genome for the most famous cell line in science: HeLa. The first cell line ever created, HeLa cells have also been the most frequently used: from testing the polio vaccine in the 1950s to current tests of drugs and compounds, these cells are part of the foundation of modern molecular biology. HeLa cells are also a story of communication failures between researchers and the "human subjects" whose samples are studied. Henrietta Lacks -- after whom the cells were named -- was a black tobacco farmer who died in 1951; her tumor tissue was taken and grown without her knowledge or consent. It was decades before her family learned about the cells, and they were frustrated by paternalistic treatment and being kept in ignorance. The story is told in excellent detail in Rebecca Skloot's book, "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks."

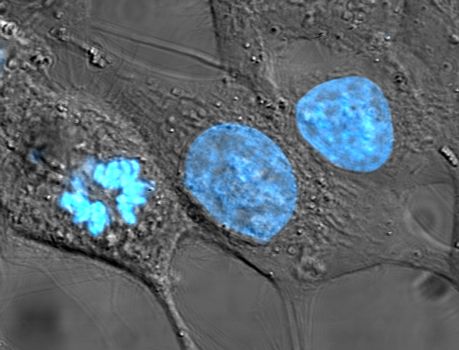

[caption id="attachment_1088" align="alignright" width="300"] HeLa cells with fluorescent stain.

HeLa cells with fluorescent stain.

CC0 from Wikipedia.[/caption]

With such a history, we might expect extra sensitivity when researchers perform major research on this cell line. Unfortunately, this was not the case: the researchers had not contacted the Lacks family. That faux pas sparked sharp criticism from Yaniv Erlich, Jonathan Eisen, and Rebecca Skloot. A widespread outcry arose, demanding more respect for the human subjects from whom cell lines are derived. And yet we should understand the researchers didn't do something particularly special: Joe Pickrell pointed out that HeLa's genetic information had been published for some time through projects like ENCODE.

We are noticing the elephant in the room: cell lines were collected from individuals before the modern era of whole genome sequencing. Even if some consent was acquired, little or no warnings were made regarding potential loss of privacy.

And this is where researchers throw up their hands: "Are we supposed to stop our research? Science would come to a halt if we expect this level of consent before publishing sequence data!" The research by Gymrek et al. in Yaniv Erlich's lab comes as an unwelcome confirmation of what George Church has been warning for years: genomes are identifiable and revealing. We may not be able to hide from this much longer: with direct-to-consumer genotyping services, research subjects will theoretically be able to detect when public sequence data matches their private genotyping data.

Specimens can no longer be treated as anonymous, they come from people. This is the new reality and we need to do better.

We can do better

The Personal Genome Project has been working to address this issue since its inception in 2005. Using an "open consent" process, we collect samples and data from volunteers who have made an informed decision to assume the open-ended risks associated with donating these items to be publicly available. We have a dozen PGP cell lines shared at Coriell, and there's over a hundred more that will be listed soon. When the project started years ago, many wondered how many people would volunteer for the risks of privacy loss. It turns out this fear was probably exaggerated: as I write this we have over 2500 volunteers enrolled.

But we need help, especially from fellow researchers. Here's ways you can help us create a new generation of well-consented samples and data:

- Use our samples and data -- In addition to those cell lines, we have 160 genomes and hundreds of donated genotyping datasets associated with survey data for 239 traits and diseases.

- Cite us -- At the risk of being accused of self promotion, here is the link to our 2012 paper featuring the PGP-10 and announcing other shared data and samples: "A public resource facilitating clinical use of genomes." Also useful is the 2008 paper "From genetic privacy to open consent."

- Enroll -- If you're willing to go public, you can also enroll and donate samples and data to the PGP. Many participants are fellow researchers, giving back to science in this manner.

- Ask people to fund us -- Tell people the PGP needs support and funding. We do not currently have any government funding (not even for maintenance of our website and database). It would also be wonderful to see sequencing companies and other groups contribute genome sequencing resources.

[caption id="attachment_1111" align="alignright" width="240"] License:CC-BY, by Brenda Gottsabend[/caption]

License:CC-BY, by Brenda Gottsabend[/caption]

Help wanted for cancer cell lines

In particular we could use help from a Boston-area researcher, probably with pathology experience, who is enthusiastic about joining the PGP staff as a volunteer to create well-consented cancer cell lines. We get occasional emails from participants curious about donating surgical samples but we haven't had the bandwidth to take advantage of those opportunities. It's a string of tasks, mostly small but doable: organizing tissue sample kits and collections, shipping instructions, tissue dissections, cell line establishment, and getting the resulting cell lines to Coriell.

If you’re interested in joining us to create a new generation of well-consented cell lines, get in touch!